While the main purpose of Family Manager is to help families create and follow routines, it can also be a great and interactive way to teach children about economy.

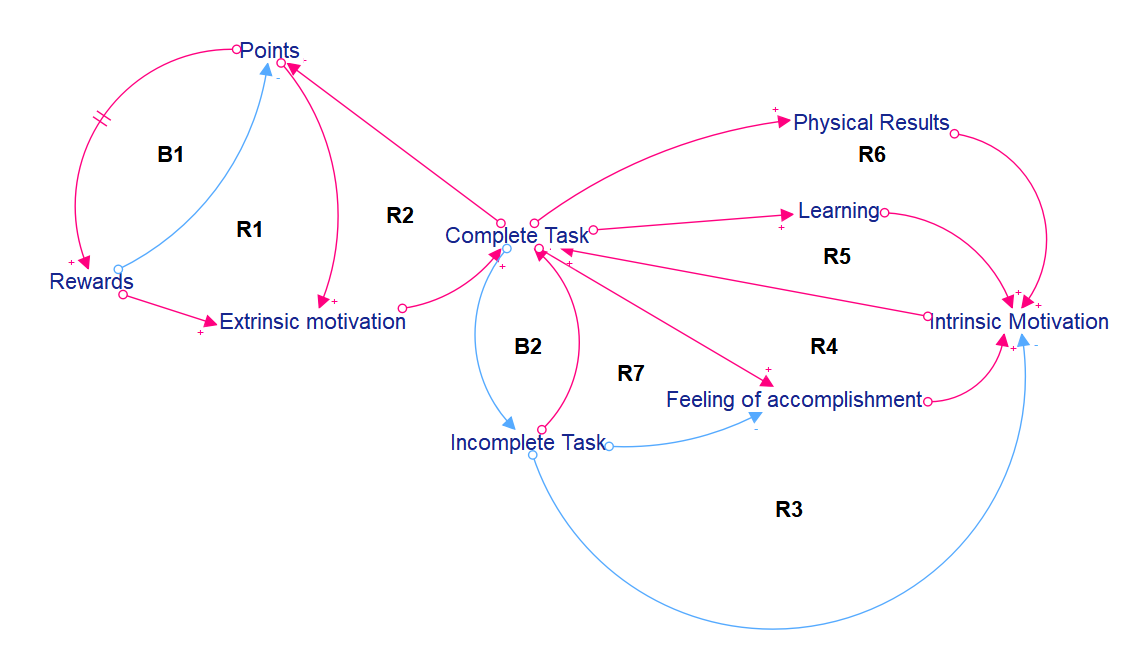

The app’s game environment operates as a local economic system within the family. Think of the points as a sort of currency. The family is given a lot of control over this system, since they determine the worth of labor and rewards themselves. This means the app can adapt to different families in different situations.

Earning points

In the app, points are earned by doing specific assignments. The child always knows what the assignment is and how many points it is worth. This mirrors our society where money is earned through labor.

According to consumer researcher Andrea Borch at the National Institute for Consumer Research (Norwegian: Statens institutt for forbruksforskning, SIFO) this approach is a good way to teach children the relationship between labor and money. Even if household-tasks later in life give no extrinsic rewards like a job would, in her experience the children will naturally understand the difference when they get older and also learn to value said household work as much as any other job (Noer, 2011, Stykkprisavtaler).

Willy-Tore Mørch, psychologist and professor of child and adolescent mental health at the University of Tromsø, agrees that children should be rewarded for completing assignments, but states that they should not get extrinsic rewards for good behavior. Parents should influence behavior through personal interactions and as role models. He also points out that both children and parents can learn a lot from negotiating and coming to an agreement on what sort of tasks should be done in the household (Nyquist, 2017). This is why we strongly encourage the family to set up task and rewards together, and make sure the parents also have their tasks set up in the app – not just the children.

Spending points

The child can spend the points they earn on rewards predetermined by the family. The specific reward and number of points it will cost mirror a real market, where people exchange money for goods and services. Unlike most economic systems, the points don’t circulate in the system like money would. They are created by parents and are removed from the system once a reward has been redeemed.

To connect the app to real life and make it easy for the child to transition to using money later in life, one could make the points resemble money, where for example 1 point = 1 NOK or 1USD. By doing this, children who are too young to freely spend money can still learn about its value. Spending 25 points to get an ice cream from the freezer at home will later feel familiar when spending 25kr to buy an ice cream in the store. This also makes it easy for parents to set up values for rewards. For example, if the child wants to save up for a new bike, a parent can set the item up as a reward where the price in points is equal to the real life price of the bike.

Once the child is old enough to start using money freely, our app supports rewards that automatically (through third party apps such as Vipps or Paypal) transfer money to the child’s bank account. This would take some of the control away from the parents, as the child can spend their money on anything, but according to Christine Warloe, consumer economist at Nordea, children need this freedom and the responsibility that comes with it, because they learn by doing and from their mistakes. If a child experiences having to stay home while all their friends are at the cinema because they spent their allowance, they might prioritize differently next time (Jørgensen, 2012, Gi dem ansvar).

Parents may still set up other rewards in the app if they so choose. This could be a good way to help the child with savings. For example giving them the choice of adding 100 points towards a bike in our app or spend those points to get 100kr added to their bank account. This way they can clearly see what their saving goal is and how close they are to it. This goal is also separated from their everyday bank account that they use for smaller sums such as lunch money or pokémon cards. This can be considered a stepping stone towards good saving habits as an adult.

It’s important to keep in mind that the rewards do not have to be related to spending real life money. Since the family decides what the rewards are they can include things such as TV or game time. However, we strongly discourage having family time as a reward. For example, going to the park as a family is a healthy habit and should not have to be earned.

This freedom means that families struggling economically can still teach their children about the relationship between labor and reward without having to spend money.

Conclusion

All in all the versatility of Family Manager makes it a good learning environment for children, where they can safely explore and help build an economic system with their family. The interactive experience and its resemblance to real life economy can help develop good saving and spending habits which can continue into adulthood.

Sources:

Jørgensen, K. K. (2012, February 9). Triksene som gir deg økonomiske barn. Retrieved March 25, 2019, from https://www.nrk.no/livsstil/laer-barna-okonomi-fra-de-er-sma-1.7986586

Noer, L. K. (2011, December 14). Lommepenger etter innsats? Retrieved March 25, 2019, from https://www.nrk.no/livsstil/lommepenger-etter-innsats_-1.7915890

Nyquist, J. (2017, May 23). Hvor mye skal barna få i lommepenger? Retrieved March 25, 2019, from https://www.santanderconsumer.no/magasinet/bedre-okonomi/barna-fa-lommepenger/